On August 14, 1945, World War II effectively came to an end with the announcement of Japan’s unconditional surrender to the Allies. Since that date, both August 14 and August 15 have been commemorated as “Victory Over Japan Day” or simply “V-J Day.” The term has additionally been used for September 2, 1945, which marks the date of Japan’s formal surrender which took place aboard the U.S.S. Missouri. With Japan’s surrender occurring several months after Nazi Germany’s, it finally brought six years of war and bloodshed to a highly anticipated end.

Attacks on Pearl Harbor, Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Japan’s catastrophic surprise attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, on December 7, 1941, was the breaking point in the increasingly hostile relations that had developed between Japan and the United States over the previous decade. The attack led to the immediate U.S. declaration of war on Japan the following day. Germany, Japan’s ally, then declared war on the United States, escalating the raging war in Europe into a large-scale global conflict. Over the course of the next three years, more sophisticated technologically and efficiency enabled the Allies to wage an increasingly one-sided war against Japan in the Pacific, inflicting severe casualties while suffering few in comparison. By 1945, as an attempt to falter Japanese resistance before resorting to a land invasion, the Allies were constantly bombarding Japan from air and sea, dropping around 100,000 tons of bombs on over 60 Japanese towns and cities between March and July 1945 alone.

The Potsdam Declaration, an ultimatum issued by Allied leaders on July 26, 1945, called for the unconditional surrender of Japan. If Japan surrendered, it was a promised a peaceful government in accordance with “the freely expressed will of the Japanese people.” If Japan refused, it would face “prompt and utter destruction.” Despite this, the Japanese government refused to surrender and on August 6, the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima, killing over 70,000 people and obliterating a 5-square-mile area of the city. Three days later, the U.S. dropped another atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, killing 40,000 people.

The next day, the Japanese government released a statement, finally accepting the terms of the Potsdam Declaration. In a radio address in the afternoon of August 15 (August 14 in the in United States), Japanese Emperor, Hirohito persuaded the Japanese people to accept the surrender, stating the use of the “new and most cruel bomb” on Hiroshima and Nagasaki as the cause of the country’s defeat. Hirohito declared that if Japan continued to fight, “it would not only result in the ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation but would also lead to the total extinction of human civilization.”

The World’s Reaction to Japan’s Surrender

In a press conference at the White House on August 14, President Harry S. Truman announced the news of Japan’s surrender: “This is the day we have been waiting for since Pearl Harbor. This is the day when Fascism finally dies, as we always knew it would.” Joyful Americans proclaimed August 14 as “Victory Over Japan Day,” or “V-J Day.”

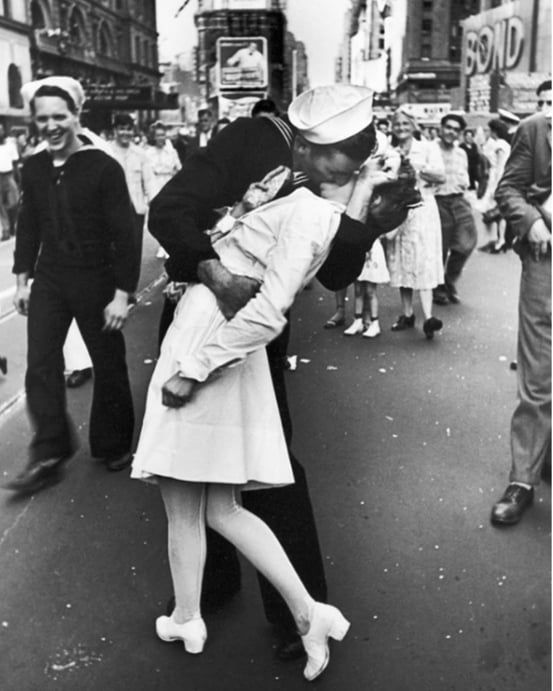

Photographs from V-J Day celebrations from the U.S. and around the world expressed the enormous sense of joy and relief felt by the citizens of Allied nations at the end of the lengthy and grisly conflict. A photograph taken by Alfred Eisenstaedt for Life magazine depicting a uniformed sailor passionately kissing a nurse amidst the crowded celebrations in New York’s Time Square became an icon of V-J Day. On September 2, the formal Japanese surrender was signed by U.S. General Douglas MacArthur, Japanese foreign minister, Mamoru Shigemitsu, and the chief of staff of the Japanese army, Yoshijiro Umezu aboard the U.S Navy battleship Missouri. This effectively marked the ending of World War II.

The Controversy of V-J Day

Over the years, many V-J Day celebrations dwindled out due to concerns over causing offense to Japan who are now one of America’s closest allies, as well as to Japanese Americans. Some also considered it disrespectful of the nuclear devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the thousands of people killed. In 1995, the 50th anniversary of the end of the Second World War, the administration of President Bill Clinton referred to the day as the “End of the Pacific War” rather than “V-J Day” in its official commemoration ceremonies. However, the decision to change the name received criticism for being overly considerate towards Japan, and disrespecting U.S. veterans who as prisoners of war, suffered immensely at the hands of the Japanese.