The Start of the Italian Campaign

The Allied invasion of Italy, codenamed Operation Husky, was a large World War II campaign in which the Island of Sicily was taken from the Axis Powers (Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany) by the Allies. Operation Husky was launched by the Allies before sunrise on July 10th, 1943 and began with a massive amphibious and airborne attack on the southern shores of Sicily.

Following the defeat of Germany and Italy in the North African Campaign (November 8th, 1942 – May 13th, 1943), the dominant Allied powers, the United States and Great Britain planned the invasion of occupied Europe and the ultimate defeat of Nazi Germany. The Allies decided that their next step would be a major initiative against Italy, with a hope to eradicate their fascist regime, secure the central Mediterranean and divert German defenses from the northwest coast of France where the Allies intended to target in the future. The Italian Campaign was launched with the Allied invasion of Sicily which after 38 days of fighting, successfully drove Italian and German troops out of the island and the U.S. and Great Britain prepared to attack the Italian mainland.

With the Allied victory in North Africa on May 13, 1943, more than 250,000 Italian and German troops surrendered in Tunisia. The Allied leadership was faced with two options of how to proceed with further action; to launch a cross-channel attack into northern France, or to attack southern Italy, which was described by British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill (1874-1965) as “the soft underbelly of Europe.”. After intense debate, the U.S and Great Britain decided to attack the Italian island. Sicily was a stepping- stone into mainland Italy and the Allies could count on fighter cover from British air bases in Malta for a Sicilian invasion.

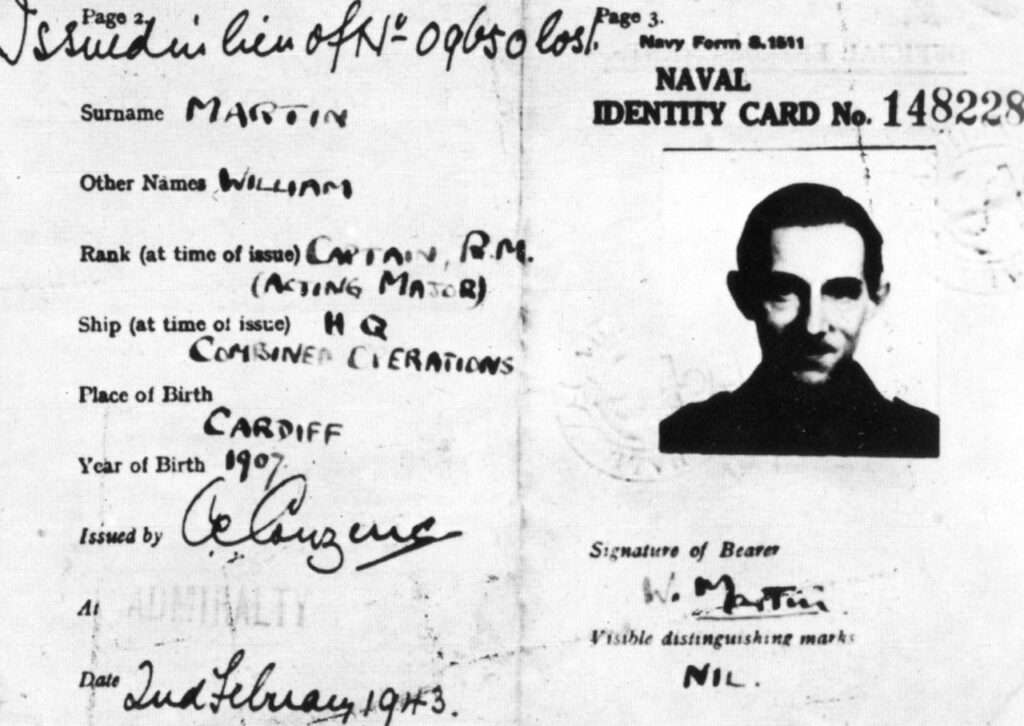

Operation Mincemeat

The invasion was not without a little subterfuge. One month before the Allied victory in the North African Campaign, the body of a British Royal Marine pilot, Major Martin William, was recovered by Germans from the water off the Spanish coast. Attached to the pilot’s wrist, documents containing information disclosed what appeared to be the secret plans of an Allied attack. The documents soon reached German leader, Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) who after carefully reviewing all the details of the captured plans, directed troops and ships to the islands of Corsica and Sardinia, against an anticipated Allied invasion. However, the recovered body was not a Royal Marine but was actually a Welsh suicide victim who had been dressed by British intelligence in an elaborate diversion called Operation Mincemeat. The successful operation was designed to divert German defenses, enabling the real planned attack to go ahead.

The Allies Land at Sicily

Operation Husky was almost cancelled the previous day when a storm arose, interfering with the Allies’ ability to land paratroopers behind enemy lines. However, the summer storm also worked to the Allies’ advantage as it convinced the Axis powers that the offensive operation against them would not occur due to such bad weather conditions. On July 10th, 1943, the Allies launched Operation Husky before dawn, which was a combination of sea and air landings involving 150,000 troops, 4,000 aircraft and 3,000 ships at the Sicilian coast. As Nazi leadership maintained the belief that the main attack would occur at Sardinia and Corsica, the Allies were opposed by only two German divisions on the island. The Axis defense was also substantially weakened by the huge losses that the Italian and German armies had suffered in the North Africa, not only casualties, but also the large number of troops who were captured at the end of the campaign.

The Allies Advance

Over the course of the next five weeks, Allied troops advanced to the Sicily’s northwestern shore before heading east towards the port of Messina. As the Allies had hoped, following the invasion, the Italian fascist regime rapidly fell. On July 24, 1943, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini (1883-1945) was deposed and arrested under a new provisional Italian government set up by Marshal Pietro Badoglio (1871-1956) who immediately began discussions with the Allied governments regarding an armistice and withdrew Italian troops the following day.

Hitler, however, ordered his forces to continue fiercely battling against the Allied advance. On August 17th, 1943, the Allied armies closed in on the northeastern port of Messina, where they discovered that the Germans had evacuated more than 100,000 troops, along with ammunition, vehicles and supplies to the Italian mainland. With the enemy forces withdrawn, the invasion of Sicily was complete. Due to the relatively low number of German losses, the Allied advance against mainland Italy would prove to be much a more strenuous task, costing the Allies more troops than they had originally anticipated.

(AP Photo)

Axis Troops Withdraw from Sicily

As Patton and Montgomery closed in on the northeastern port of Messina, the German and Italian armies managed (over several nights) to evacuate 100,000 men, along with vehicles, supplies and ammunition, across the Strait of Messina to the Italian mainland. When his American soldiers moved into Messina on August 17, 1943, Patton, expecting to fight one final battle, was surprised to learn that the enemy forces had disappeared. The battle for Sicily was complete, but German losses had not been severe, and the Allies’ failure to capture the fleeing Axis armies undermined their victory. The advance against the Italian mainland in September would take more time and cost the Allies more troops than they anticipated.